Calls to lower the age for cervical screening are well-intentioned but misplaced

Posted: January 28, 2017 Filed under: NHS, Sexual Health | Tags: cancer, cervical cancer, HPV, screening Leave a commentIt may seem timely that this year’s cervical cancer prevention week (Jan 22nd – 28th) fell just days after the latest petition calling for lowering the age for cervical cancer screening began circulating online. The petition followed the tragic death of 25-year-old Amber Cliff who passed away earlier this month after a four year battle with cervical cancer. Her death and the petition – signed by nearly 200,000 people – made headlines in the papers after it was revealed that Amber had asked for a smear test from her doctor after experiencing vaginal bleeding and abominable pains but was told, at 21, she was too young. Since her death, campaigners have been calling for screening to be made available to women younger than the current recommended age of 25. It’s not the first petition of its kind but, although these campaigns are started with only the best intentions, the truth is lowering the screening age may not be the solution to preventing further deaths of women like Amber.

To understand why, it’s important to know what exactly the cervical screening test is designed to do. The screening tool is not a test for cancer; rather it is designed to spot women at risk of developing cancer. Since October 2016 the way the screening test does this is by identifying cases of human papilloma virus (HPV). HPV is a viral infection that can cause genital warts, abnormal tissue growth and other changes to cells within the cervix and it is very common among women under 25. Most cases of HPV will clear up on their own but sometimes the cell abnormalities can lead to cervical cancer. In fact, the vast majority of women with cervical cancer will have had an HPV infection. So, lots of women have it and will never get cervical cancer but those who have cervical cancer have probably had it.

As HPV is so common among women under the age of 25, if this group were screened then many would be flagged up for further investigation, including possible having parts of the cervical tissue cut away. As doctors cannot tell which abnormal cells will clear up by themselves and which may develop into cancer, the discovery of any HPV may lead to women having this procedure, which is what current advice suggests. In most cases, it would be completely unnecessary. This is an important point because a systematic review of research found this procedure leads to an increase risk of pre-term birth during later pregnancies (although the risk may be lower for excisions less than 10mm deep). So the argument against lowering the screening age is that women who are not at risk of developing cancer would undergo a procedure that increases their risk of delivering pre-term babies.

However, women over 25 with a HPV infection and cervical cell abnormalities that have not cleared up by themselves are believed to be more at risk of developing cervical cancer. Therefore, the removal of cervical tissue in these cases seen as a necessary risk.

But that’s only half the story of cervical cancer. Following the introduction of HPV vaccine for teenage girls, HPV infections will be much rarer going forward. With fewer women carrying HPV infections, the needs and use of cervical cancer screening may change. It is also worth noting that testing for HPV infection became the primary aim of screening only late last year (it is still being rolled out across England). Previously, the primary aim was to identify abnormal cells and then test for HPV. National guidelines for screening age have been repeatedly examined in recent years, reiterating support for the minimum age of 25, but these have yet to be looked at in the context of HPV testing as the primary aim. No doubt they will be assessed again in the future and new evidence may lead to recommendations being adjusted.

This does not do much, however, to soothe the grief of Amber Cliff’s family, nor anyone else who has lost a young daughter, sister or girlfriend to cervical cancer. Cervical cancer is rare in the general female population and even more so among women that young – but it does happen.

In their 2010 review into the appropriate age for cervical cancer screening, the Advisory Committee on Cervical Screening (ACCS) concluded there was strong evidence supporting the minimum age of 25 but made clear that:

“…a significant proportion of cervical cancer cases in women under 25, women who visited their GP with abnormal bleeding, experienced a delay in diagnosis because they did not receive a full pelvic examination.”

And although headlines and campaigns tend to focus on calls to lower the screening age, many of those who have lost loved ones to this disease recognise that the problem is often more to do with recognising symptoms. Over six years later, Amber’s brother Josh is calling for the same thing the ACCS highlighted in their report. He told the Sunderland Echo he is not necessarily campaigning for routine screening for 18-year-old women but for extra vigilance among doctors whose patients show similar symptoms to Amber. For those who do show symptoms, the smear test used for screening the over 25s would not be appropriate but they may benefit from a pelvic examination.

Although recognising that doctors face a difficult task keeping up to date with guidelines and advice on countless health problems, perhaps the question isn’t about what age we should be screening women, but why might a doctor might not send a young women for a pelvic or specialist examination when she presents with vaginal bleeding and abdominal pains?

Tackling malaria by mapping internal migration

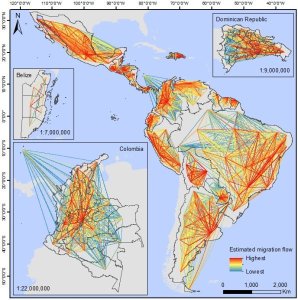

Posted: August 23, 2016 Filed under: Global Health, Malaria, Technologies and innovation | Tags: global health, infectious diseases, low income countries, malaria, middle income countries 2 CommentsAs part of a project looking at preventing the spread of infectious diseases, a bunch of researchers have produced maps visualising how people move around countries with high malaria rates.

The maps produced by geographers at the University of Southampton show internal migration in Africa, Asia and Latin America and the Caribbean, focusing on low and middle income countries.

“Understanding how people are moving around within countries is vital in combating infectious diseases like malaria,” said Professor Andy Tatem, Director of WorldPop university mapping project.

“Understanding how people are moving around within countries is vital in combating infectious diseases like malaria,” said Professor Andy Tatem, Director of WorldPop university mapping project.

“Having an accurate overview of how different regions of countries are connected by human movement aids effective disease control planning and helps target resources, such as treated bed nets or community health workers, in the right places.”

The data on internal migration was gathered through census data in forty different countries.

The next stage of the project involves integrating the migration estimates with data on malaria prevalence. It is hoped that this could help to inform regional elimination and global eradication plans for the disease.

Government’s obesity plan described as ‘massive damp squib’

Posted: August 18, 2016 Filed under: NHS | Tags: diet, NHS, nutrition, obesity, preventative care 1 CommentThe government announced today a long-awaited plan to tackle childhood obesity – but the “watered-down” proposal seems to only have left a bad taste in people’s mouths.

Instead of proposing regulations on how sugary products can be advertised to young people – which had been included in earlier drafts – the plan asks the food and drink industry to voluntarily cut sugar in products.

The voluntary target is a 5% cut to the sugar in products popular with children over the next year, with the ultimate target 20%. The plan also includes proposals to get schools to make sure children have 30 minutes of exercise a day.

The best estimate we have of the cost of obesity – mainly as a result of the cancer, diabetes and heart disease it causes – is around 27 billion GBP a year (although as the ever-brilliant Full Fact point out the data behind these are a bit old and uncertain).

But from Jamie Oliver to former Health ministers, everyone is a bit disappointed with what’s being described as a “damp squib” of a policy. One of the biggest questions is whether companies will actually do anything to meet a voluntary target.

A similar initiative with salt years ago suggests it could be possible. Over ten years ago, a collaboration with the food industry to get salt levels down – with voluntary targets and strict monitoring of the companies – was successful for a few years.

Sonia Pombo, from the Campaign for Consensus on Salt and Health told the BBC’s You and Yours programme today that voluntary targets for sugar levels could also work “provided it was done in the right way.”

“Unfortunately, this obesity plan looks weak and watered down,” she said. One of her main concerns is that responsibility for monitoring the sugar levels will fall to the government’s Responsibility Deal, which she says has failed to monitor salt levels since taking over the remit a few years ago.

High satisfaction with NHS care among cancer patients – but home care needs improvement

Posted: August 11, 2016 Filed under: NHS | Tags: cancer, home care, hospital care, integrated care, NHS, primary care, secondary care Leave a commentEvery year the government commissions a survey of people with cancer to find out their experiences of being cared for by the NHS. The results from the latest research were published a few weeks ago, showing overall high levels of satisfaction among cancer patients about the care they received.

Over 87% of respondents said that, overall, they were treated with dignity and respect in hospital, with 78% saying they were definitely involved as much as they wanted to be with decisions about their care.

There were also positive findings regarding the involvement of Clinical Nurse Specialists, with 90% of those asked saying they were told the name of a Specialist who would support them and 87% saying it had been “very easy” or “quite easy” to get in touch with them.

However there are obvious areas for improvement. Although many people said they were told about told about support groups and entitlements to free prescriptions, only 55% said that hospital staff gave them information about how to get financial help or any benefits they might be entitled to.

There were similar low responses to questions about home care. When the cancer patients were asked if doctors or nurses definitely gave their family or someone close to them all the info they needed to help care for them at home, only 58% said that happened. Only 54% said they definitely received enough care and support from health and social services such as district nurses, home helps or physiotherapists during their cancer treatment.

Lack of integration?

Although they can only tell us so much, these statistics suggest the handover from hospital-based secondary care to community or home-based primary care is not as smooth as it could be. This may tie into the need for better integrated health and social care in the NHS. Although the benefits of better ‘integrated care’ have been recognised for decades it has only started to take centre-stage in NHS policy in recent years. How this might look in reality is still a work in progress.

The big government financing programme to explore better integrated care takes the form of the Bigger Care Fund announced in 2013. This involves the transfer of 5.6bn pounds from NHS to a pooled health and social care fund for new integrated care initiatives. The work on this has only really just started in the past few years and it will take time before its successes and failures reveal themselves. However it has not been without controversy – from a financial perspective, the government’s own Audit Office projected it would save less than a third of the amount projected at best and might not even do the job it set out to do.

Study confirms the older you are, the wiser you become

Posted: August 10, 2016 Filed under: Just for fun Leave a commentA study that involved getting people to estimate how steep a hill is may have confirmed the long-held belief that people get wiser with age.

Researchers at Swarthmore College in the United States asked 50 young students and 50 adults from the nearby area to estimate the steepness of a hill near the college.

According to the research lead Professor Frank Durgin, people tend to over-estimate how steep a slope is – even estimating a 5 degree slope as 20 degrees.

In their latest research they found that those who had some knowledge about slope gradients – such as those who did downhill skiing – were more accurate with their guesses about the slope.

Interestingly, they also discovered that older participants gave estimates similar to those from the ‘knowledgeable’ participants. “Even if the older participants did not report having any specific knowledge, it still seemed like their life experience had made them better estimators,” Durgin said.

Although it’s a pretty low sample size, the study findings contradict previous beliefs that hills might look even steeper to older people.

“Our findings are probably surprising to many because of the widespread belief that things like ageing can make the world look different,” he said.

“But the perception of the geometry of the world, in itself, doesn’t seem to be affected by ageing, apart from possible effects of lost acuity.”

“[Older adults] seem to have acquired wisdom with their years about the difference between how thing seem and how things are. This is a point well worth making.”

UK teen pregnancy success story threatened by cuts

Posted: April 20, 2016 Filed under: Sexual Health | Tags: contraception, pregnancy, Sexual health, teen pregnancy Leave a commentWith the rate of teenage pregnancy in England halving since the government’s ambitious Teenager Pregnancy Strategy was launched in 1998, the programme is widely viewed as a public health success story.

It should rightly be celebrated. Any drop in the number of teenagers falling pregnant, who if they went on to have children would be less likely to take up further education and employment opportunities, is a good thing.

A look at the figures shows that as the numbers have fallen, however, the stark differences in the rate of conception between poorer and richer areas of England have persisted. In 2004, the most deprived 20 percent of local authorities in England saw, on average, 56 conceptions per 1,000 girls aged 15–17. This compared to 25 in the 20 percent least deprived. Another way of looking at it, for every single girl pregnant in the richer areas, 2.24 would conceive in the poorer areas.

Using more up-to-date data, this ratio gap grows slightly. Taking the latest government data on the 20 percent most and least deprived local authorities – available up to 2014 – and comparing it to 2015 data on pregnancy among 15-17-year-old girls, we can see that for every pregnant girl aged between 15 and 17 in the areas with least deprivation, there are now 2.54 girls getting pregnant in the most deprived areas.

This correlation between deprivation and teenager conception is no new thing. Research carried out by the Office for National Statistics has long examined this correlation, and also shown a link between high unemployment rates and child poverty with under 18 conception rates.

Why is there a link between deprivation and teen pregnancy?

One reason for this is the perception of motherhood held by young women. A study carried out back in 2004 by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation concluded that ‘young women who perceived their lives as insecure were more likely to view motherhood as something that might “change their life” in a positive way. Those who were certain that their future life would develop through education and employment were more likely to opt for abortion.’

Other reasons include personal factors such as low self-esteem, lower educational and occupational aspirations, less knowledge of contraception and sexual health services and higher gender power differentials’, according to one ONS report from 2002.

“Easy access to sexual health services is also likely to have a role,” explains Senior Policy and Public Affairs Officer Laura Russell at the sexual health charity Family Planning Association. “There is a correlation between good contraception services and lowering rates of teenage conceptions.”

The impact of local authority budget cuts

Since the 2012 government reforms, improvements in health – including contraceptive services – have largely fallen under the remit of local authorities, paid for by a ring-fenced budget. Following the announcement from the Treasury earlier this year that public health budgets for councils are to be cut by 7 percent – or 200 million – some medical organisations have been concerned about the wider impact this will have on conception and healthcare in general.

Plus with councils of less well-off areas less able to raise significant funds through council tax, as suggested by the Treasury, people living in these authorities might be disproportionally affected.

The Advisory Group on Contraception (AFG), an expert group of clinicians and advocacy group, argue that cuts to contraceptive care in primary care settings means there will be “tighter restrictions on who can access the service and what contraceptive methods are available”.

Using figures provided by the Department for Health, they point out that there is an £11 saving for every £1 spent on contraception, arguing it is “a false economy” to cut funding to this area.

However, a survey carried out by AFG in 2014 found that around a third of local authorities reported having no plan in place to reduce the rate of unintended pregnancies, leading to concerns it is not being prioritised. A spokesperson for the group also confirmed that an update to this survey is due to be published later this year.

The British Medical Journal has also carried out investigations into the impact of public health cuts on sexual health services. For those with access to BMJ articles (not me!), you can find more details here.

Sexual and reproductive healthcare is a basic human right – for undocumented migrants too

Posted: April 7, 2016 Filed under: Sexual Health | Tags: migrant healthcare, Reproductive health, sexual healthcare, SRHR, undocumented migrants Leave a commentDespite the right to sexual and reproductive health being well established in EU international human rights instruments, they are – along with many others – frequently denied to undocumented migrants.

I’ve previously written about the problems undocumented migrants have trying to access healthcare here. While researching that piece, it became clear there is a gulf between rights enshrined in international law and policies implemented at a national level. Often care for undocumented migrants depends on the extent of engagement from local government and healthcare groups, who often are best placed to recognise the significant cost savings that can be made by providing preventative care.

Of this group, women in need of sexual and reproductive healthcare are – along with children – arguably the most vulnerable. According to the Platform for International Cooperation on Undocumented Migrants (PICUM), they are disproportionately affected by high rates of maternal and infant mortality, limited access to contraception and pregnancy termination, and heightened levels of discrimination and gender-based violence, including at the border, in transit and in detention.

PICUM say deficiencies of policy and practice on sexual and reproductive health in the EU have been thrown into sharp relief by the recent arrival of millions of refugees and migrants to the continent.

“The desperate trip across borders brings an untold number of new dangers for vulnerable women and girls – violence, rape, sexually transmitted infections, unintended pregnancies, unsafe abortionn,” said Caroline Hickson, Regional Director, International Planned Parenthood Federation (IPPF) Europe. “Access to essential sexual and reproductive health services can be the difference between life and death. Yet it is still shamefully neglected in response strategies. If we value women’s lives, it must move from afterthought to priority.”

An undocumented woman from the Philippines, living in Denmark, shared her experience: “Throughout the course of my pregnancy in Denmark, I did not visit a doctor. I was afraid, because I was in the country without permission. So I continued my work as a cleaner. I went to the hospital only when the pain was unbearable. The labour was already advanced. There was so much blood. I had a caesarean section, but the baby did not survive. She died in an incubator. But I did see my daughter, I have a photograph of her. I named her Claire*. She is buried in Copenhagen.”

A few weeks after giving birth, the woman was deported from Denmark after she was reported by hospital staff to immigration officials.

PICUM’s are now calling for countries to reform legislation and policies that deny or limit access to sexual and reproductive health services on the basis of residence status.

It also urges governments to establish a ‘firewall’ to delink the provision of basic services, including sexual and reproductive health services, from immigration control. In practice, this requires limiting the sharing of personal data between health care providers and immigration enforcement authorities to ensure that patients can access care without fear of being denounced or deported.

To read PICUM’s latest report on the topic, click here.

World AIDS Day: The worst messages sent to HIV positive guys on dating apps

Posted: December 1, 2015 Filed under: Global Health, HIV/AIDS | Tags: dating, discrimination, HIV, stigma, World AIDS Day Leave a commentIt’s December 1st, which means…it’s World AIDS Day. This year I wanted to share this funny and revealing video from the gay men’s health charity GMFA. They got a bunch of guys to read out messages sent over a dating messaging app to HIV+ men. The results suggest even though education about HIV has come along way, stigma and misinformation is still a problem faced by many.

Bringing morphine to millions

Posted: November 23, 2015 Filed under: Global Health, Technologies and innovation | Tags: Africa, cancer treatment, HIV, hospice care, pain medication, pain relief, palliative care, Uganda Leave a commentThe following article was originally published on Think Africa Press in December 2012. The site has since closed down but since this topic is a very important one and continues to be close to my heart, I wanted to republish it again here:

Bringing morphine to millions

For people with difficult health conditions which cause them unrelenting pain, only the strongest form of relief can allow them to live an anywhere near comfortable life. For many in the West, the cheap and plentiful opioid morphine provides this respite. But for millions elsewhere, this essential relief is yet another denied right.

Frank, a 49-year-old Ugandan man, had been living alone with an open tumour on his neck, abandoned by his family because of the stench caused by his illness. He had not slept or eaten in weeks because of the pain.

Frank was fortunate enough to be found by a community volunteer worker from Hospice Africa Uganda (HAU). He was referred to the hospice team, who treated his would, and he was shown how to use oral morphine. Soon after, his family returned to continue his care.

“He was able to eat a little, sleep a little more, and settle his affairs before he died in peace, with his family and pain-free three weeks later”, Zena Bernacca, CEO of the hospice, tells Think Africa Press. “Having pain relief makes a real difference; otherwise one’s whole existence is narrowed down to suffering unimaginable pain, obliterating everything else.”

Relief from pain also allows for time to address other social and emotional needs, such as future childcare or religious wishes. For Frank, the palliative care and morphine provided by HAU meant that he could be with his family.

“I have slept for the first time in many weeks”, he told hospice care workers shortly before his death. “This wound is clean and no longer smells. I have my family back and I have food to share. I am blessed.”

Essentially lacking

Considered essential by the World Health Organisation (WHO), morphine costs relatively little to provide. But 80% of the world’s population lacks access to this treatment. In fact, where demand is highest, access to pain relief is at its lowest. Low- and middle-income countries, which account for 70% of cancer deaths and 99% of HIV-related deaths, consume just 6% of the world’s medicinal opioids.

“Pain relief is a central component to palliative care”, says Dr Emmanuel Luyirika, Executive Director of the African Palliative Care Association. “Without the immediate release of oral morphine, it’s impossible to manage moderate to severe pain.”

According to a 2010 survey conducted by the International Narcotics Control Board, the major reasons given by governments for the low availability of opioids include fears of addiction, a reluctance to prescribe, and insufficient training for professionals.

“There’s an issue of strict regulations in countries based on unfounded fear of abuse, but also limited understanding of palliative care at most levels of policy, service provision and community within those countries”, explains Luyirika.

Setting a trend

However, a number of models of pain treatment in Africa have allowed palliative care on the continent to grow, providing opportunities for governments and organisations to collaborate and learn.

Hospice Africa Uganda offered the earliest model designed for the African setting. Founded by Dr Anne Merriman in 1993, HAU has long provided oral morphine for a growing numbers of patients. Two years ago it broadened the reach of this drug significantly when Uganda ran out of stock. Encouraged by The Global Action for Pain Relief Initiative (GAPRI), an NGO working to spread awareness of palliative care methods, the hospice tendered for the contract and has since been selling stocks to the Ugandan government for national distribution.

Uganda also overcame another obstacle by becoming the first country to train nurses to prescribe morphine. Previously only doctors could prescribe the drug, making it impossible to meet demand. Routine meetings and training allow the hospice to alleviate any staff worries about misuse, and staff can in turn placate any fears from patients and families.

“Out of ignorance, so many are concerned about potential addiction”, explains Bernacca. “However, once there is an understanding of how morphine works as a painkiller, and that when used appropriately it does not cause addiction, the patient is relieved. And the majority of carers are also relieved of the distress of witnessing such pain.”

Along with programmes in Tanzania, Kenya and Zimbabwe, this public/private partnership is now a model of morphine production, and other countries are following suit. Research into palliative care and pain relief on the continent is still lacking, but these programmes are building understanding of how such care can be incorporated alongside other African health policies.

“These palliative care programmes are helpful because they show us what is possible”, says Dr Meg O’Brien, Director of GAPRI. “They provide models that can be adapted to other programmes, and they give us evidence about the cost and impact of services that we can use to help leaders in other African countries make more informed decisions about what kind of care is achievable.”

Obstacles on the road

Indeed, the complexities of supplying morphine mean that in many African countries political will is not enough. GAPRI has consistently found governments to be keen to provide pain relief services, but hampered by technical and bureaucratic barriers.

Pain treatment does not sit easily in one area of healthcare, and this can cause questions about department responsibility. Moreover, an effective programme requires cooperation among disparate groups that include policymakers, training institutions, hospital administrators, drug procurement bodies, financing offices, clinical guidelines committees and drug regulators.

“Sorting out the necessary collaborations is time-consuming, and many governments simply lack the capacity to push changes through quickly”, says O’Brien. GAPRI addresses this by helping ministries of health with research, chasing paperwork, consultations and consolidating data. Founded only two and a half years ago, the organisation is young and still small, but its rapid development reflects a growing interest in pain treatment.

As calls increase for non-communicable diseases (NCDs) to be included in any post-2015 sustainability goals, palliative care and pain relief programmes could offer an initial achievable step in this direction. Uganda has only one radiotherapy machine, which is held together with sticky tape. Scaling up resources to combat the increasing incidence of NCDs requires a long-term strategy and significant funding. Pain relief programmes offer opportunities to expand into this area and start bridging the false divide between communicable and non-communicable diseases.

“Rather than distract ministries, I think an initial focus on palliative care actually focuses efforts”, suggests O’Brien.

“Provision of modern pain relief and palliative care is a ‘low-hanging fruit’. It can be done using existing funds and resources and will have an immediate benefit for cancer patients and others who suffer pain. I see it as an ideal starting point for ministries to expand care for NCDs while the international NCD community works on expanding funding and staff.”

Reblogged from The Wire: India Must Resist US Pressure on Generic Drugs, African Leaders to Tell Modi

Posted: October 28, 2015 Filed under: Global Health, Technologies and innovation | Tags: drug policy, generic medicines, pharmaceuticals Leave a commentThis explainer from journalist MK Venu writing for the Indian magazine The Wire talks us through the pressures on the Indian government from US pharma and African governments, representing both sides of the generic medicine debate:

In his ‘Mann ki baat‘ radio show on Sunday, Prime Minister Narendra Modi proudly spoke about how India will host 54 heads of state from Africa for the first time to reinforce “our nation’s historical and cultural links’ with African countries.

However, invoking this very spirit, the visiting African leaders will place before the Prime Minister an issue of life and death for their peoples in which India can play a critical role – the export of cheap and affordable generic medicines for the cure of AIDS and other deadly diseases. The African heads of state will urge Modi to resist growing pressure from the United States government and Western drug multinationals on India to stop exporting cheap generics to Africa.

Journalist and Writer

A blog by the students enrolled in P11.181 Introduction to Global Health Policy at NYU-Wagner

Thoughts and rants from another angry woman

For researchers, students, activists and anyone interested in research on sex work and related topics, including human trafficking

The blog of the European Association for Palliative Care

global health policy issues